Every era of easy money produces its speculative mascots. In the late 1990s, it was Beanie Babies — tiny stuffed animals that cost under a dollar to make, yet sold for hundreds to thousands. The Princess Diana memorial bear that once fetched more than $60,000 now goes for around $3; one variant, Peanut the Royal Blue Elephant, once a $5,000 trophy, now sells for about $6. At the height of the craze, these toys accounted for 10 percent of all eBay listings. Their boom coincided perfectly with the late-1990s dot-com melt-up, a period defined by suppressed interest rates, rapid credit expansion, and rampant speculation. When the tech bubble burst in 2000, the Beanie Baby market had already collapsed — a micro-indicator of distorted price signals and misallocated capital.

A full generation later, the same underlying forces have produced the newest collectible frenzy: Labubus. Made by Chinese toymaker Pop Mart, these demonic-looking plush figures were sold in “blind boxes,” injecting a gambling-like payoff structure into retail purchases. For much of the past year, drops sold out instantly. Secondary-market prices rocketed: a limited-edition Vans Old Skool Labubu sold for $10,585, and a unique four-foot-tall version went for $170,000 in China. Counterfeits proliferated, and stores faced crowds, shouting matches, and physical brawls. Even Forbes briefly labeled the toys “good investments.”

But the correction has now arrived. Only months after its enthusiastic coverage, the same Forbes writer issued an update: prices were falling, inventories rising, and attention shifting elsewhere. Today, none of the 60 priciest Labubus on eBay has significant bids. And, as one middle-schooler put it succinctly, “they’re not that cool anymore.” The wall may have already been hit.

This pattern will feel familiar to readers of an earlier analysis of COVID-era collectible markets. As previously pointed out in our article on the “Pokéflation,” massive monetary expansion — stimulus payments, PPP funds, lockdown savings, and near-zero interest rates — drove Pokémon card prices up tremendously from 2020 through 2022. Professional grading services amplified the mania, valuations soared into the tens or hundreds of thousands, and speculative participation surged. That earlier piece traced how artificially suppressed interest rates mimicked an increase in real savings, misleading producers and consumers alike. The result, as Austrian theory predicts, was widespread malinvestment — new projects, longer production structures, and frenzied bidding in assets ranging from stocks and crypto to trading cards.

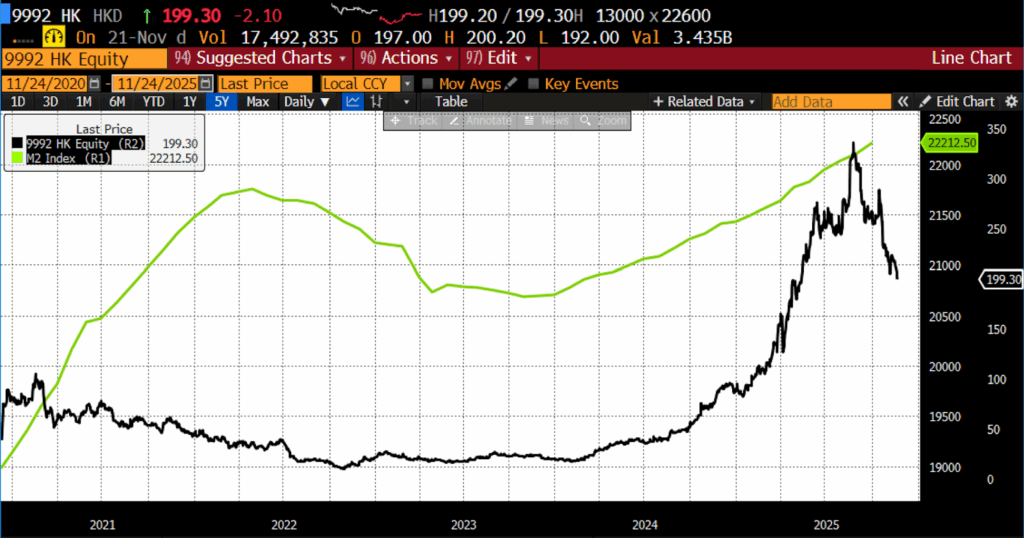

Pop Mart stock price (9992 Hong Kong) and US Money Supply M2, 2000 – present

The subsequent bust unfolded exactly as the Austrian explanation suggested. As rates rose in 2022 and credit contracted, asset prices slid broadly. The S&P 500 fell more than 20 percent, the NASDAQ nearly 30 percent, and Bitcoin dropped from $65,000 to below $19,000. NFT markets collapsed. A Holographic McDonald’s Pikachu card that once sold for $51 dropped to $16.88, a 67 percent decline. Jack Dorsey’s first-tweet NFT went from $2.9 million to $280. The BITA NFT Index fell 68 percent, and has declined consistently. As that earlier article argued, these corrections were the necessary liquidation of projects and valuations sustained by monetary illusion rather than genuine shifts in consumer time preferences.

The same monetary distortions that propelled Pokémon card prices and crypto valuations upward have pushed speculative enthusiasm into ever-more-marginal corners of consumer culture.

Viewed through that lens, the Labubu phenomenon is less of an isolated cultural oddity than the next chapter in the same story — a minor but telling update to what was previously observed in Pokémon cards, NFTs, and other speculative submarkets. The same monetary distortions that propelled card prices and crypto valuations upward have pushed speculative enthusiasm into ever-more-marginal corners of consumer culture. When plush dolls trade hands at used-car prices, the underlying issue isn’t the toys themselves, but the environment producing the bidding frenzy.

If the broader asset bubble deflates (further), the policy response is predictable: rapid rate cuts and another round of extraordinary quantitative easing. But as Austrian theory warns, and as earlier episodes repeatedly confirmed: monetary manipulation merely postpones the reckoning and intensifies the next cycle of errors.

Are Labubus the new Beanie Babies? In the narrow sense, yes. But more importantly, they are a small, harmless reminder — an update, really — of the same deeper dynamic previously pointed out: easy money distorts choices, inflates curiosities into “investments,” and turns even plush toys into bellwethers of a monetary system addicted to perpetual stimulus.