Introduction

The minimum wage is one of the most frequently debated economic policies of the modern era. Advocates argue that it protects low-income workers from exploitation and ensures a livable wage. Critics contend that it distorts labor markets, reduces employment opportunities, and can contribute to inflation.

This explainer offers a comprehensive analysis of the minimum wage, exploring its history, mechanics, intended goals, and real-world economic impact. We will also examine common criticisms and misconceptions about the minimum wage from a free-market perspective.

The History of the Minimum Wage

The idea of a government-mandated minimum wage first emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, under the ideological sweep now known as the Progressive Era. New Zealand was the first country to implement a national minimum wage (1894), followed by Australia (1907). In the United States, the minimum wage became law with the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, which set a national wage floor of $0.25 per hour (about $5.50 in 2024 dollars). The law aimed to prevent employers from paying substandard wages, particularly during the Great Depression.

Over time, the US minimum wage has been adjusted repeatedly, both in nominal terms (actual dollars and cents) and in response to inflation (to adjust for lost purchasing power). Many other countries have taken similar steps, though the specifics vary widely. Some nations, such as Switzerland and Sweden, have no statutory minimum wage, instead relying on industry-specific wage agreements negotiated through collective bargaining.

How the Minimum Wage Works

At its core, a minimum wage law establishes a legally binding floor on wages, meaning employers cannot pay workers below a certain hourly rate. Certain employers may be exempt from minimum wage laws, such as small businesses with fewer than a specified number of employees, those hiring seasonal or agricultural workers, and family-owned businesses where only immediate relatives are employed. Additionally, exceptions often apply to tipped workers, student workers, and certain disabled employees under specialized wage programs, allowing employers to pay below the standard minimum wage under specific conditions.

The intent, as typically stated, is to ensure that even the lowest-paid jobs provide a basic standard of living. The minimum wage does not operate in a vacuum, however. Its effects depend on broader economic conditions, labor market dynamics, and the relative bargaining power of employers and employees. When a minimum wage is set above the market equilibrium rate—the wage at which supply and demand for labor naturally balance—it can lead to unintended consequences, such as reduced employment opportunities and increased automation.

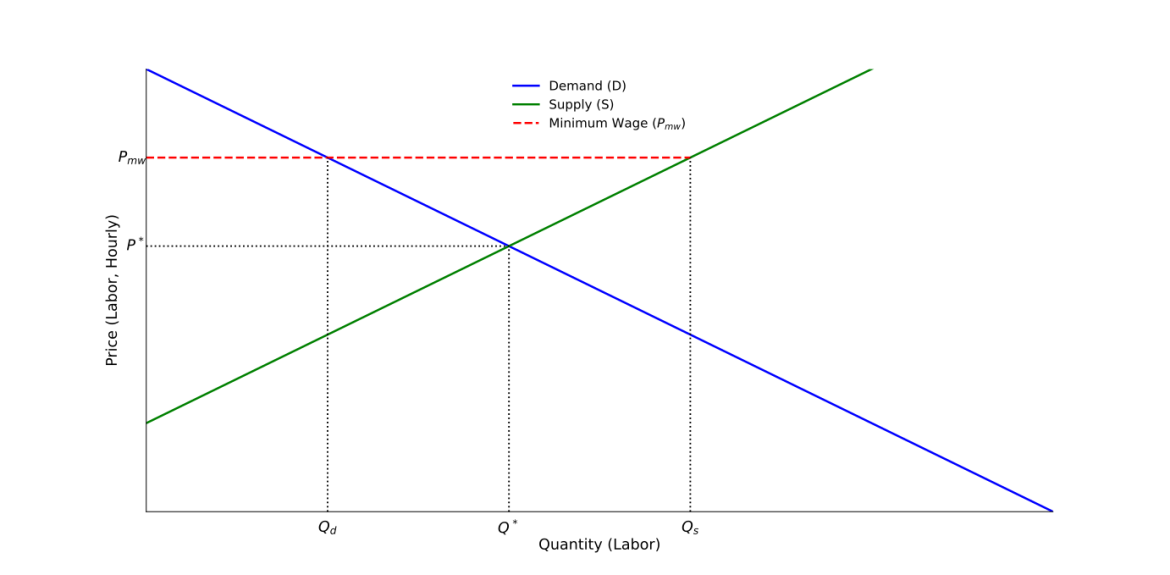

The economic explanation is found in the graph below:

When a minimum wage (Pmw) is set above the market equilibrium wage (P*), a labor surplus is generated. At the equilibrium price (P*) and quantity (Q*), labor supply and demand are balanced. However, at the higher mandated wage (Pmw), the quantity of labor supplied (Qs) exceeds the quantity of labor demanded (Qd), resulting in excess labor—commonly referred to as unemployment. The discrepancy reflects the reduced hiring incentives for employers and the increased willingness of workers to enter the labor market at the elevated wage level.

The Minimum Wage in the United States

In the United States, the federal minimum wage is set by Congress and applies to most workers covered under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). As of 2024, the federal minimum wage remains at $7.25 per hour, a level unchanged since 2009. Individual states, however, have the authority to set their own minimum wages above the federal level, and many have done so to reflect local cost-of-living differences. As of March 2025, the highest state minimum wage is in Washington, at $16.28 per hour, while the lowest federal level remains in states that have not enacted their own higher wage laws. Some cities, such as Seattle and San Francisco, have implemented even higher local minimum wages.

Employers are legally bound to comply with the highest applicable wage—whether federal, state, or local—ensuring that workers receive the maximum legally mandated amount in their jurisdiction.

What the Minimum Wage Actually Does

Economists have extensively studied the effects of minimum wage laws, and findings indicate that the policy often comes with trade-offs. Here are some of the primary impacts of a minimum wage:

Sets a Floor on Labor Costs

A legally mandated minimum wage forces employers to pay at least a specified amount, regardless of the productivity or skill level of the worker. When businesses are legally mandated to pay higher wages, they may compensate by reducing other forms of compensation, such as benefits, bonuses, or training opportunities. Furthermore, industries with low profit margins (retail, food service, hospitality) are disproportionately affected, as they rely heavily on low-wage labor. These increased labor costs result in higher prices for consumers, potentially offsetting the intended benefits of wage increases.

Reduces Employment

When a minimum wage is set above the market rate for specific jobs, it creates a price floor that can lead to labor surpluses—commonly referred to as unemployment. Employers may find it too costly to hire as many workers as they otherwise would, particularly those in entry-level or low-skilled positions. This is especially concerning for small businesses, which often operate on tight budgets and cannot absorb higher wage costs as easily as large corporations. Empirical studies on this issue have produced mixed results, but many show that increasing the minimum wage leads to job losses, particularly among young and less-experienced workers. Over time, this effect can contribute to higher structural unemployment and reduced workforce participation.

Incentivizes Employers to Hire Fewer Workers and Work Them Harder

To maintain profitability amid rising labor costs, employers often adjust their workforce strategy by hiring fewer employees and increasing the workload of those who remain. This means existing workers may face greater job demands, longer shifts, and increased pressure to be more productive. While some employees may appreciate the extra hours, others may experience burnout, stress, and reduced job satisfaction. Additionally, businesses may shift toward employing fewer full-time workers and instead rely on part-time or temporary staff to reduce costs. This can make it more difficult for employees to secure stable, long-term employment with non-wage benefits such as health insurance and retirement contributions.

Encourages Automation

As the cost of human labor rises, businesses have a stronger incentive to invest in automation to perform tasks previously done by low-wage workers. This trend is particularly evident in industries like fast food, retail, and manufacturing, where self-checkout kiosks, robotic food preparers, and automated customer service software are increasingly replacing human employees. While automation can improve efficiency and reduce business costs, it also reduces opportunities for low-skilled workers to gain entry-level jobs that provide essential work experience. Over time, this shift can exacerbate income inequality by favoring highly skilled workers who design and maintain automated systems, while eliminating opportunities for those with fewer skills.

Distorts Market Signals

In a free-market economy, the price of labor functions as a key signal to allocate labor resources efficiently. When wages are artificially set above equilibrium levels, businesses and workers receive distorted signals about labor supply and demand. For example, high minimum wages can lead to an oversupply of workers seeking jobs that no longer exist, while discouraging investment in industries that might otherwise create more employment opportunities. Furthermore, businesses may relocate operations to regions with lower labor costs or invest in outsourcing, reducing domestic job availability. These distortions lead to unintended consequences and inefficiencies, such as labor shortages in specific sectors and persistent unemployment in others.

Hurts Marginal Workers the Most

One of the most concerning effects of high minimum wages is their disproportionate impact on marginal workers—those with the least experience, lowest skill levels, or the greatest barriers to employment. Young workers, immigrants, and individuals with limited education often struggle the most to secure jobs when wage floors are high, as employers prioritize hiring more experienced or highly skilled workers. This can create long-term economic disadvantages, as job seekers are unable to gain the experience necessary to move up the career ladder. Additionally, minority and disadvantaged communities are often hit hardest by minimum wage hikes, as they tend to have higher unemployment rates and greater dependence on low-wage jobs for workforce entry.

Ignores Business Heterogeneity

A mandated minimum wage assumes a one-size-fits-all approach to labor costs, ignoring the vast differences in business structures, profit margins, and financial resilience across industries. A large multinational corporation can often absorb higher wage costs with relative ease, while small businesses with lower revenue streams may struggle to remain viable. This disparity can trigger market consolidation, where only larger firms survive, reducing competition and innovation. Additionally, regional cost-of-living variations make a federal wage policy particularly problematic, as a rate that is feasible in a high-cost metropolitan area may be unsustainable in a rural town.

Variables Affecting the Impact of a Minimum Wage

The economic impact of a minimum wage increase depends on several key variables. One of the most important factors is the size of the jump from one increase to the next. When minimum wages (labor costs) rise significantly over a short period, businesses have less time to adapt, which can lead to employment reductions, automation, or price increases. Another factor is the frequency of increases; more frequent but smaller adjustments can allow employers to gradually adapt, whereas infrequent but large jumps tend to create economic shocks. Finally, the gap between the prevailing average wage in a state or locality and the new minimum wage is critical. If the minimum wage is already close to the median wage, the impact on employment is likely to be small. However, if the minimum wage is significantly higher than what many workers currently earn, businesses may struggle to absorb the cost increases, leading to job losses or cutbacks in hours. These variables shape how disruptive a given minimum-wage policy is to labor markets.

The Card Krueger Findings

One of the most well-known studies on the minimum wage was conducted by economists David Card and Alan Krueger in the early 1990s. Their research examined the impact of a minimum wage increase in New Jersey’s fast-food industry, comparing employment changes to neighboring Pennsylvania, where the minimum wage remained unchanged. Their findings suggested that, contrary to conventional economic theory, the wage increase did not lead to a reduction in employment and may have even slightly increased job numbers.

While Card and Krueger’s study has been widely cited by minimum-wage proponents, its findings are highly context-dependent. The study focused on a specific industry (fast food) in a limited geographic region and covered a relatively modest wage increase ($0.80). Additionally, factors such as local labor market conditions, employer responses, and data-collection methods have been subjects of debate. Later research, using more comprehensive datasets and improved methodologies, has produced mixed results, with many studies confirming that higher minimum wages tend to reduce employment, particularly among low-skilled workers. Thus, while Card and Krueger’s findings contribute to the discussion, they do not establish a universal principle applicable to all minimum wage increases.

Common Assertions Regarding Minimum Wage Laws

“Raising the minimum wage will reduce poverty.”

While higher wages benefit those who remain employed, job losses among the least skilled workers often offset these gains. Moreover, many low-wage workers are not in poverty (e.g., teenagers from middle-class families), and many impoverished individuals do not work at all. Direct cash transfers, earned income tax credits, and job-training programs are often more effective poverty-reduction tools.

“Minimum wage increases boost the economy by increasing worker spending.”

Although higher wages may increase spending for some workers, the net economic impact is unclear. Higher labor costs force businesses to raise prices, cut jobs, or reduce investment, which can counteract any demand-side stimulus. Moreover, mandated wage hikes do not create new wealth—they simply redistribute it, often inefficiently.

“Businesses can easily absorb higher wages by reducing profits.”

Many small businesses operate on thin profit margins and cannot simply absorb higher wages without making other adjustments. Large corporations may be better positioned to handle wage hikes, but small businesses—which employ a significant portion of the workforce—may struggle to remain viable.

“Raising the minimum wage will reduce reliance on government assistance.”

While some workers may rely less on social welfare programs after a wage increase, others will lose jobs or see their hours cut, potentially increasing their need for assistance. Additionally, higher wages do not address underlying issues such as high living costs or a lack of affordable housing.

“Other countries have high minimum wages without major job losses.”

Countries with high minimum wages often have other policies that offset their impact, such as lower payroll taxes, less-restrictive labor regulations, or stronger apprenticeship programs. Moreover, countries with stronger productivity growth can sustain higher wages without adverse employment effects.

“Minimum wages ensure fair pay, otherwise employers would pay excessively low wages.”

The idea that a legislated wage floor ensures fairness ignores that wages naturally adjust to reflect worker productivity. In competitive labor markets, employers must offer wages that attract and retain employees. If a worker’s productivity does not justify the minimum wage, employers are incentivized to automate or eliminate the role entirely, reducing opportunities for low-skilled workers.

“The minimum wage helps lift low-income workers out of poverty.”

While higher wages help some workers, minimum wages often lead to job losses, particularly for young and inexperienced employees. Rather than lifting people out of poverty, a minimum wage increase can push marginal workers into unemployment, and trap others by removing the bottom rung of the employment ladder. Targeted policies such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) are more effective in assisting low-income workers without distorting labor markets.

“Minimum wages stimulate consumer spending, and workers with higher incomes are likely to spend more, boosting demand in the economy.”

Though higher wages may increase individual spending, the broader economic impact cannot be ignored. Employers facing higher labor costs may offset these expenses by reducing jobs, cutting hours, or raising prices. The net effect can neutralize or even reverse any perceived boost in overall consumer spending.

“By setting a higher wage floor, minimum wages may reduce worker exploitation and turnover.”

While higher wages may reduce turnover, they also lead employers to increase workloads for existing employees and impose stricter hiring requirements. This disproportionately harms low-skilled workers who rely on entry-level jobs as stepping stones to better employment. A freer labor market allows for more diverse job opportunities and career progression.

“Raising the minimum wage lifts the earnings of the lowest-paid workers, thereby reducing income inequality.”

Artificially raising the wage floor compresses the wage distribution, but does not address underlying skill gaps or barriers to upward mobility. Instead, it discourages investment in workforce training and makes it harder for low-skill and entry-level workers to gain employment. Economic growth driven by innovation and productivity gains is a more sustainable way to reduce inequality than wage mandates.

While outside the main focus of this discussion, it’s worth briefly considering whether the wage gap merely reflects variations in skill, experience, and other factors, and if efforts to narrow it might unintentionally cause more harm than benefit.

Recent Findings

Recent studies have examined the effects of minimum wage increases on various demographic groups, including young people, individuals with low skill levels, and minorities. Key findings include:

- General Employment Effects: A comprehensive meta-analysis by Neumark and Shirley (2021) found that 79.3 percent of studies reported negative employment effects following minimum wage hikes, with the impact being more pronounced among teens, young adults, and less-educated workers.

- Impact on Young Workers: Research by Kalenkoski (2024) indicates that minimum wage increases can lead to reduced employment opportunities for young, unskilled workers. A separate study highlighted that a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage could result in a decrease in employment rates among this group.

- Effects on Low-Skilled Workers: Newmark (2018), focusing on the least-skilled workers, finds strong evidence that minimum wage increases can lead to job losses in this demographic.

- Influence on Minority Employment: National Bureau of Economic (NBER) research suggests that race differences in employment effects of minimum wages could be more pronounced when considering low education and skill levels. The study specifically found evidence that higher minimum wages led to greater job losses among black workers compared to other racial groups.

- On-the-Job Training Reduction: A study by Neumark and Wascher found that a 10 percent increase in minimum wages decreased on-the-job training for young people by 1.5 to 1.8 percent, potentially hindering skill development and future earnings.

These findings underscore the complex and varied impacts of minimum wage policies across different segments of the labor market. Pushing on one economic lever has varied effects, many of them unintended.

Conclusion

The minimum wage remains a contentious policy. While well-intended in its aim to protect workers and alleviate poverty, a minimum wage generates significant trade-offs that should not be ignored. Minimum wages artificially raise labor costs, which can lead to unintended economic distortions, including reduced employment opportunities, increased automation, and higher consumer prices. Small businesses, which often operate on thin profit margins and for which labor comprises a high percentage of total operating expenses, are particularly vulnerable to these changes and may be forced to lay off workers or reduce hiring.

Additionally, minimum wage laws disproportionately harm those they are intended to help, such as young, low-skilled, and minority workers, by making it harder for them to gain entry-level employment. Employers facing increased wage costs often respond by cutting hours, eliminating benefits, or raising performance expectations, which can make work more demanding without necessarily improving overall job satisfaction. Rather than fostering broad-based prosperity, rigid wage floors risk excluding the most vulnerable from the workforce altogether.