For decades, America’s manufacturing sector has seemingly eroded, with jobs and production shifting overseas in search of lower costs and fewer regulatory constraints. While many companies have relocated abroad, the reality is more nuanced than it appears. Certain industries have declined, but US manufacturing output has fluctuated rather than collapsed outright. By some measures, total output has remained stable or even grown. For instance, US manufacturing output in 2021 reached $2.5 trillion, an 11.55 percent increase from 2020. A more accurate depiction of manufacturing trends suggests that while employment in the sector has fallen, productivity gains and technological advancements have prevented an absolute decline in output.

Nevertheless, domestic manufacturing has been in relative decline for decades, making it a convenient political talking point. Recently, the concept of a “Mar-a-Lago Accord” has emerged — a theoretical framework aimed at restructuring the international financial system to benefit US interests.

Key proponents, including Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and economic adviser Stephen Miran, suggest that such an accord could reduce US debt and revitalize domestic manufacturing by weakening the dollar, lowering borrowing costs, and attracting investment — all while maintaining dollar dominance. This plan would involve persuading foreign trade partners to cooperate, swapping US bonds for long-term, non-tradable debt, and potentially using US assets as collateral. However, securing such international cooperation could lead to unintended consequences, including rising domestic borrowing costs and higher consumer prices. But the lynchpin of all of that is purposeful, politically-motivated, dollar depreciation.

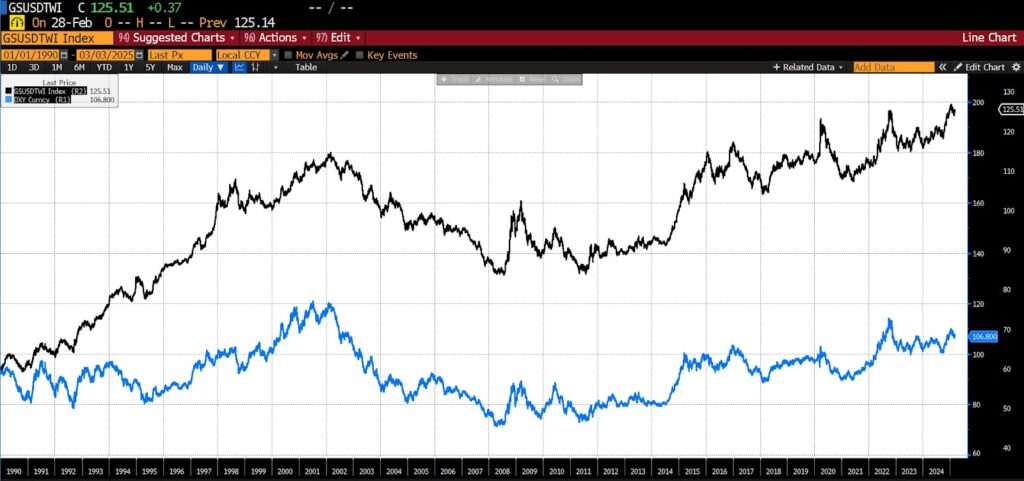

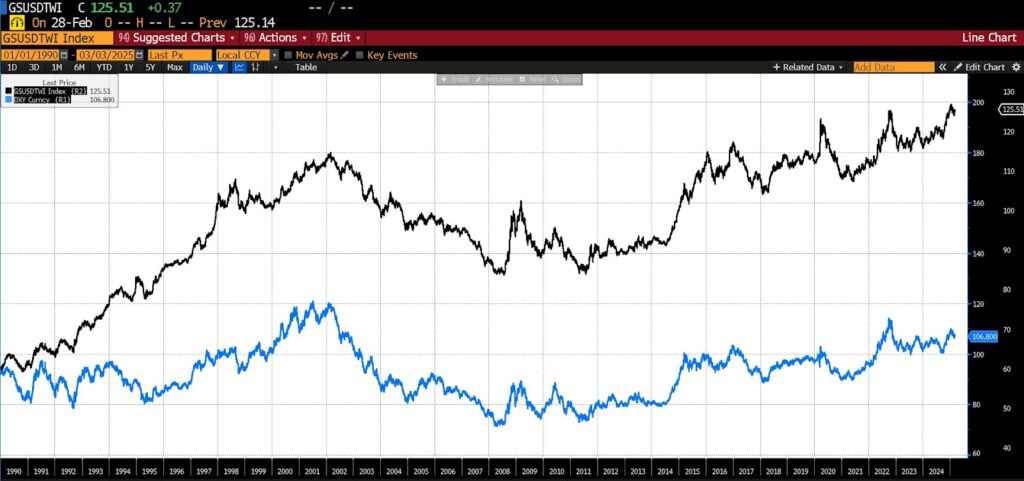

The US Dollar Index vs. the Trade-Weighted Dollar

To fully assess the dollar’s strength since the end of the Cold War, the most relevant metric is the trade-weighted US dollar (TWUSD), which considers exchange rates with a broader range of trading partners, including China and Mexico — two of the largest recipients of outsourced American manufacturing. In contrast, the more commonly cited US Dollar Index (DXY) primarily tracks the dollar against a limited basket of six currencies (euro, yen, British pound, Canadian dollar, Swedish krona, and Swiss franc) and fails to capture broader trade dynamics.

Trade-Weighted US Dollar (black) vs. the US Dollar Index (blue), 1990–present

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the trade-weighted dollar index has risen over 110 percent, making US exports more expensive globally while making imports cheaper. As the financial sector has gained dominance, domestic industries competing with foreign firms have faced increasing pressure.

Proponents of a weaker dollar argue that devaluation would make US exports more attractive while raising import costs, thereby incentivizing domestic production and consumption. However, currency devaluation alone does not enhance the quality or competitiveness of goods; it simply manipulates prices. As a National Bureau of Economic Research study notes, currency undervaluation can influence comparative advantage, but its impact varies widely depending on broader economic conditions.

Devaluing the Dollar: Shortsighted and Ineffectual

Even if America were to beat the dollar down as a first step toward embracing an all-out industrial policy aimed at reviving manufacturing, the transition would take decades — likely generations. And over the course of those years the economic landscape is likely to shift unpredictably multiple times: new technologies, global shifts in shifts, and financial crises, each of which inexorably alters the global landscape. At the same time, the successful accomplishment of the reshoring of manufacturing to the US would require an improbable number of other things – access to cheap and reliable energy and efficient raw mineral sources, for example – to remain the same or improve.

If the US dollar is to be the focus of policy, a more broadly beneficial approach would be to prioritize long-term stability over persistent inflationary pressures, ensuring a sound monetary foundation for both investment and economic growth. The Federal Reserve’s inflationary bias has played a pivotal role in facilitating the shift away from toward financialization. If the Fed were restricted to a single mandate of maintaining a stable dollar with a zero percent inflation/deflation target, it could reduce the outsized emphasis on financial markets. Curbing excessive liquidity-driven asset inflation and making financial markets less dependent on Fed intervention would tacitly encourage capital to flow into productive, long-term investments rather than speculative financial assets.

Politicians should attempt to be honest about the realities of reshoring. As difficult as it may be to accept, Americans may need to adapt to and navigate the realities of today’s economic landscape rather than attempting to recreate the unique, long-gone conditions of the 1960s. While browbeating the dollar might provide a temporary boost to exports, it is no silver bullet. Instead of looking for quick fixes and promising overnight rejuvenation of a bygone era, a more productive focus seeks market-based solutions that enhance innovation, investment, and global trade.

The Structural Challenges of a Weaker Dollar Strategy

For decades, America’s primary exports have been the dollar itself–actual dollars, US Treasury bonds, and dollar-denominated financial assets–rather than physical goods. China, Japan, Germany. Mexico, Canada, and other major trading partners have accepted dollars in exchange for their exports, fueling America’s consumption-driven economy. Those dollars have been invested in US Treasuries, enabling the massive pile of debt that now threatens America’s economic heath and national security. Undoing that long-established arrangement would require much more than just a weak dollar — it would necessitate a complete reorganization of the US economy away from financialization.

Even if the process of shifting resources away from financial products into brick and mortar goes smoothly, industrial power won’t return within one or two presidential terms; certainly not overnight. America has spent decades deindustrializing, and much of the required physical infrastructure, supply chain establishment, and cultivation of a skilled labor force essential for large-scale production will have to start anew. Reviving these components requires far more than currency manipulation.